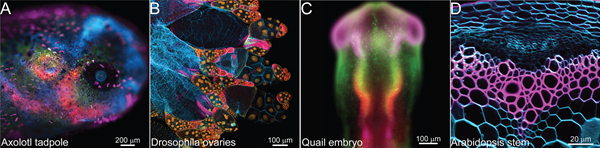

The authors of today's developmental biology textbooks face the challenge of keeping up with a field in which the number of published papers is staggering and which is increasingly fragmenting into sub-disciplines, such as developmental neurobiology, developmental cell and molecular biology, stem cell biology and Evo-Devo. The other challenge when writing an introductory textbook is to decide what to cover without going into too much detail.FIG1,FIG2

Essential Developmental Biology, Second Edn By Jonathan M. W. Slack

Blackwell Publishing (2005) 365 pages

ISBN 1405122161

£29.99 (paperback)

Principles of Development, Third Edn By Lewis Wolpert, Thomas Jessell,Peter Lawrence, Elliot Meyerowitz, Elizabeth Robertson and Jim Smith

Oxford University Press (2006) 551 pages

ISBN 0-19-927536-X

£34.99 (paperback)

Two textbooks from eminent British developmental biologists, which have successfully dealt with these challenges and which have been around for some years, have recently published new editions: Jonathan Slack's 2nd edition of Essential Developmental Biology, and Lewis Wolpert's 3rd edition of Principles of Development, which is co-authored by several other high calibre developmental biologists - Thomas Jessell, Peter Lawrence, Elliot Meyerowitz, Elizabeth Robertson and Jim Smith. It is interesting to compare how they differ in their approach, in particular since both target a similar readership, namely undergraduate and new graduate students, and have a similar goal in mind, to distill the Essentials (Slack) or Principles (Wolpert et al.) and present them in a compact and concise way. Both books are meant to be introductory and require no prior knowledge of the subject, and they compete with several similar textbooks on the market by Scott Gilbert (Developmental Biology), Alfonso Martinez Arias and Alison Stewart (Molecular Principles of Animal Development) and Fred Wilt and Sarah Hake (Principles of Developmental Biology).

It is unfair to compare too closely each book's coverage of the field, as Slack's Essentials is almost 200 pages shorter than the 550 page book by Wolpert et al., which is a bit surprising given that both cost around£30 in paperback. Slack's textbook appears even more overpriced given that it reproduces almost no photographs, unlike that of Wolpert and colleagues. This is a shortcoming of Essential Developmental Biologybecause photos give a more realistic idea to a student (who may never see embryos in a practical course) of what a particular phenomenon or tissue being described looks like. What Slack decided to sacrifice entirely given these page constraints is the development of plants and of the lower eukaryotes,other than Drosophila and C. elegans. Furthermore, most topics are dealt with in a shorter fashion by Slack than by Wolpert, or topics are not accompanied by illustrations. For example, where Wolpert and colleagues present the dorsoventral patterning of Drosophila over two pages, Slack covers this topic in one paragraph. The Nieuwkoop center gets four lines in Essential Developmental Biology and one and a half pages in Principles of Development. That said, the conciseness of Slack's book can help to focus a reader's attention and avoids sometimes confusing detail.

Principles of Development is up to date and in terms of its scope provides a comprehensive overview of the field, covering the development of plants, as well as of less `famous'invertebrates, such as sea urchins,ascidians, slime molds and Hydra. Wolpert does a particularly great job on`morphogenesis', a topic close to his heart. His approach is factual, and experimental evidence is provided for most key findings. By contrast, Slack systematically aims to derive conclusions from experimental evidence. This is very laudable, but I wonder if his main audience would appreciate this mature approach. I am afraid that much of this good intention might be lost given the reality of most university courses, from which a certain factual canon needs to be acquired, regardless of all the experimental history that led to it.

Although boxes appear in both textbooks, a particular feature of Slack's book is a box called `Classic Experiments' and another called `New Directions in Research'. Again, I wonder how useful these are for the average student,who is looking for a concise introduction to developmental biology,particularly when space is already a constraint. Furthermore, methods such as morpholinos and domain swaps may become easily outdated, just like earlier molecular methods not mentioned anymore. Molecular methods come and go, the fate map stays forever.

While writing this review, I faced a similar problem to the authors of these books when deciding whether to cover the different vertebrate model organisms one after the other or side-by-side, according to the distinctive features of embryonic development. As Slack writes in his preface, his book differs in this respect from other similar books on the market, as it keeps the organisms separate to avoid confusing the student, who might think that`knockouts can be made in Xenopus' and the like. This approach does have a lot going for it, especially for beginners, and makes his chapters and writing very clear. Conversely, in Principles of Development, the patterning of the vertebrate body plan is covered side by side in two chapters dedicated to `Axes and germ layers' and `The somites and early nervous system'. By doing so, Wolpert and colleagues try to minimize the other common cause of confusion to students, when they are confronted with different nomenclatures in vertebrate models and need to memorize a plethora of seemingly differing phenomenology, while they are told in the first lecture that a key aspect of animal development is its evolutionary conservation. Alas, how could these authors succeed, where the field itself fails! Wolpert's`Summary Table' on `Vertebrate Axis Determination' reads as if lower vertebrates and Amniotes evolved on different planets. As another example, the parallels of limb/wing development in vertebrates and insects are hardly discussed. This may have to do with the fact that Principles of Development has become a multi-author book. In addition, various parts of the book have apparently been more or less amended by various experts in the field. For example, the writing of Claudio Stern in the chick neural induction section is unmistakable. All of this makes for very precise and up-to-date factual presentations, but it makes integration much more difficult. This is why Principles of Development reads a bit like a mosaic, whereas Essential Developmental Biology is made from one casting.

Most of us who teach developmental biology present in our early lectures the basic concepts of determination and specification relative to cell fate,and of course both authors go to great length to introduce these concepts. However, these terms hardly appear later on in these books, and, if I reflect on my own lectures, then the same holds true, as I don't use them when I discuss the various model organisms. The reason for this is that specification and determination are concepts from a pre-molecular era. We now refer to marker genes becoming induced at certain stages, without mentioning specification or determination in the classical sense. Similarly outdated may be the distinction between regulative versus mosaic development, terms intimately connected to induction. We know now that inductive processes occur in C. elegans just as much as they do in vertebrates, and that regulative versus mosaic development reflect experimental design more than fundamental biological differences. New editions of these textbooks may want to take into account this conceptual progress, particularly as both books are very molecular in their approach. Another complex term that is covered in both books is the zoo type, which remains conspicuously lifeless in Wolpert et al.'s book, whereas Slack, who originated the concept, illustrates it convincingly.

Essential Developmental Biology provides a highly readable,well-structured and nicely illustrated book. To the novice, but also to the more initiated, I would recommend Principles of Development

When covering such a broad field, certain omissions, typos, errors and the like are always likely to occur. Although Slack had to sacrifice covering certain topics because of his space constraints, certain terms should nevertheless have been explained or discussed. For example, `neural induction'is missing in the index, and the Evo-Devo chapter fails to introduce`neoteny'. Given Slack's explicit aim to write also for medical students, the absence of any reference to human embryos is a shortcoming. Teaching experience shows that referring to human congenital malformations is always very stimulating for students. Principles of Development extensively discusses vertebrate organogenesis, but the authors do not seem to be very fond of endodermal derivatives. The index of Principles furthermore lacks the important terms `hypomorph' and `cell polarity'. Moreover the statement in this book that the mouse node is unable to induce forebrain is outdated (see Kinder et al.,2001). Finally, hyphens in certain species' gene and protein symbols should be avoided, as recommended by various nomenclature committees,and no attention has been paid to this issue in either book.

A great feature of Principles of Development is the website that accompanies it, where one can download the illustrations featured in the book. This online resource used to be freely accessible but is now unfortunately password protected. To register for access to this website, you must now be a lecturer at a teaching institution and have adopted this textbook for one of your courses. The website is very extensive, with well-organized web links to every chapter for those who want to learn more, and which feature multiple choice and concept questions to use to check a student's understanding. Although the web companion to Essential Developmental Biology is less extensive, it features many nice animations that will be useful for teaching. The site also features `Student review questions and instructor resources',which can be accessed at an extra cost of £10.

Given their different approaches and scopes, to whom would I recommend these books? To the student who takes an introductory course in developmental biology and who wants to focus on the basics, Slack's Essential Developmental Biology provides a highly readable, well-structured and nicely illustrated book. Slack's ability to present an integrated view of the field and his ability to simplify complex issues is an impressive aspect of this book. To the novice, but also to the more initiated, I would recommend Principles of Development, as its generous, multi-color illustrations make it a great learning companion. It is a very comprehensive book, which is loaded with information, including some of the latest findings on various hot topics. It does justice to its aim of outlining the key concepts and principles of development.